The opportunities provided by the CDM and future carbon trading in se Asia*.

GIOVANNI RIVA◊ - MAURO ALBERTI♦

Abstract

A policy for energy

utilisation of biomass to be effective must primarily ensure economic viability

of projects. In this sense also complementary financing mechanisms (e.g. CDM or

other Kyoto programmes) can be applied to increase financial viability of

projects. Nonetheless, also other complementary policies (research on crops,

research and demonstration of conversion technologies, standardisation of

biofuels/waste, agriculture/forestry plans and regulations, plants authorisation

procedures) are extremely important to create the conditions for a real growth

of biomass sector. Therefore, all these arguments should be considered in detail

also when analysing problems and opportunities for the development of biomass

energy in SE Asia. Particularly, the issue of tariffs to be established for

biomass electricity is extremely relevant and needs to be studied thoroughly.

Keywords: renewable energy, CDM, biomass projects, carbon credits.

1.1 Introduction

The matter considered here is the “Clean Development Mechanism”,

which is part of a package of measures that were agreed at Kyoto in 1997 by 200

countries to limit the growth of emissions to atmosphere of gases (carbon

dioxide, methane, etc.) emanating from the combustion of fossil carbonaceous

fuels (coal, mineral oil, “natural gas”, etc.)1.

CDM is an important issue for European Renewable Energy Policies insofar as it

is to be utilised by European actors (companies and national governments) to

promote renewable energy (and other) projects in developing countries to reduce

GHG emissions. In fact, the European carbon market is EU-wide but taps emission

reduction opportunities in the rest of the world through the use of CDM and JI (see

below). A key option to reduce world-wide environmental impact (i.e. greenhouse

gases) of energy production is indeed the application of proven and efficient

technologies for biomass conversion in countries where the projects for

emissions reductions can be decidedly less costly (in terms of investment/cost

per unit of CO2 reduction, €/t) than within European States. Moreover,

this opportunity could lead to penetration of European (clean) technologies in

different parts of the world, enhancing the situation of the European renewable

technologies sector.

In this sense, the European Union Member States will probably in the next years

look at countries in SE Asia as potential hosts of CDM projects that could lead

to significant and cost-effective GHG emissions reductions and to corresponding

carbon credits to be used in EU market.

1.2 Flexible mechanisms introduced in the Kyoto protocol

In Rio de Janiero in 1992, the United Nations agreed a Framework Convention

on Climate Change (UNFCCC). Representatives of the countries that are parties to

that Convention then met annually to develop secure mechanisms to counter

climate-change, while taking due account of the many complex issues raised2.

Five years later this process of development led to the “Kyoto Protocol”,

which represents a binding commitment by its signatories to take specified

actions. It set quantified targets for emissions of GHG in developed countries,

and established the “Kyoto Mechanisms” (KM) to provide means for

developed countries to meet those targets and, at the same time, to assist

developing countries.

Those developed countries that have ratified the Protocol and thereby accepted

emissions-reduction targets, may meet those targets by a combination of

activities within their own boundaries and those covered by the KM, which fall

into three categories:

Joint Implementation (JI);

(a) CDM; and

(b) International Emissions Trading (IET).

JI allows a country that has, under the Kyoto Protocol, accepted a reduction in

emissions (Emission reduction unit – ERU) of GHG, or a target for limitation of

such emissions (a so-called “Annex-1 country”), to meet part of its

obligations by carrying out eligible activities in another Annex-1 country.

CDM is similar, but allows an Annex-1 country to meet part of its obligations by

carrying out eligible activities in developing countries that have not accepted

obligations under the Kyoto Protocol (i.e. non-Annex-1 countries). Those

activities entail the development and implementation of projects that will

result in reductions of emissions of GHG overseas, thereby generating credits

for Certified Emissions Reductions (CER) that can be sold on the carbon-market (see

Section 2.2), and which can therefore provide extra income-streams for

developers.

1.3 The development and implementation of CDM projects

To be accepted within the agreed framework for CDM, projects must be

developed within the following step-wise framework (Figure 1).

In general terms, the aim for developers is to find a particular contest in

industrial/civil sectors (energy generation, waste management, specific

industrial sectors, like iron and steel, cement, glass, ceramics as well as

paper, etc.) in which, by applying an innovative (e.g. renewable) technology,

GHG reductions are obtained and the project can earn credits for CERs.

Figure 1: Project cycle of CDM.

Therefore, a preliminary step to undertake a CDM project is to assess project

additionality with respect to current conditions.

"A CDM project activity is additional if anthropogenic emissions of

greenhouse gases by sources are reduced below those that would have occurred in

the absence of the registered CDM project activity.“

CDM – Executive Board (EB, UNFCCC/CCNUCC3)

defined a "Tool for the demonstration and assessment of additionality", which is

dated October 22nd 2004. Scheme proposed by EB is presented in

Figure 2.

Figure 2: Additionality scheme proposed by EB

A wide range of technologies may be considered in the context of CDM projects

and, certainly in the case of the more complex technology-trains, a more

thorough study may be necessary to establish feasibility. Furthermore, a check

must be made to ensure that the proposed project fully complies with any

requirements imposed by the host-country.

If the feasibility-study indicates that it is possible in principle to develop a

CDM project, the next step is to prepare a Project Design Document (PDD4)

to set out the following information:

A general description of the activity.

(a) The baseline case (see above).

(b) Duration of the project/period expected for earning CER.

(c) The methodology and plan for monitoring.

(d) Calculation of emissions of GHG from the various relevant sources.

(e) Environmental impacts.

(f) Comments from stakeholders.

If there appears to be no methodology that has already been approved by UNFCCC

for assessing (a) the baseline case, and (b) the proposed improved project, in

terms of its emissions, the developer must propose a new methodology to UNFCCC

for its approval. The same requirement for approval by UNFCCC applies also to

the methodology and plan for monitoring.

Developers will also be required to provide information about the environmental

impacts of each project, including trans-boundary impacts where applicable. In

those cases where there may be significant impacts, a full Environmental Impact

Assessment must be undertaken, and the report submitted to UNFCCC.

The next step for the developer is to submit the PDD for validation to a “designated

operational entity” (DOE) that has been approved by UNFCCC. If the

methodology that has been used for the baseline case is one that has already

been approved by UNFCCC, the DOE will validate it immediately. But, if a new

methodology has been proposed, the DOE will submit this and the rest of the PDD

to the UNFCCC’s CDM Executive Board (EB) for review and approval.

The whole process of preparing and submitting for approval the PDD can be

handled by the developer or by specialised consultants5.

Registration of approved projects signals formal acceptance of them by the EB.

This is a prerequisite for the verification, certification and issuance of

certificates for “certified emission reductions” (CER).

After approval, the project must be implemented in accordance with the PDD,

including all aspects of monitoring set out therein.

The monitored reductions in emissions of GG must be periodically determined and

verified by another DOE (i.e., except in the case of small projects, a DOE that

is independent of the validator), which will then certify those reductions in a

report to the EB, which will then issue the CC accordingly; the CC can then be

sold into the market.

1.3.1 Methodologies for CDM Projects

At UNFCCC site it is possible to see a complete list of methodologies

presented for CDM projects (http://cdm.unfccc.int/methodologies/PAmethodologies).

Some methodologies have already been approved by CDM Executive Board, while

newly proposed methodologies are continuously being evaluated through a

multi-stage process (see ANNEX A).

1.3.2 Methodologies for small scale CDM project activities

The Marrakech Accords6

establish the possibility of introducing fast-track modalities and procedures

for small-scale projects, recognising that the sustainable development benefits

of these projects can be high but that these projects may not have the economies

of scale or levels of emissions reduction that larger projects enjoy7.

The definitions of small-scale projects, set out in the Marrakech Accords, are

as follows:

1. Renewable energy project activities with a maximum output capacity equivalent

of up to 15 MW (installed or rated capacity8);

type I category covers renewable energy projects including: Solar, wind, hybrid

systems, biogas or biomass, water, geothermal and waste.

2. Energy efficiency improvement project activities which reduce energy

consumption on the supply and/or demand side, by up to the equivalent of 15 GWh

per year; type II covers supply side projects and end-use projects including

residential, service, industry, transport, agricultural machineries and

cross-cutting technologies which result in improvement in per unit power for the

service provider or in reduction of energy consumption in watt hour in

comparison with the approved baseline.

3. Other project activities that reduce anthropogenic emissions by sources and

that directly emit less than 15 kilotonnes of CO2 equivalent per year. Type III

covers agricultural projects, fuel switching, industrial processes and waste

management. Possible examples in the agricultural sector include improved manure

management, reduction of enteric fermentation, improved fertilizer usage or

improved water management in rice cultivation.

In order to reduce transaction costs for small-scale CDM, modalities and

procedures are simplified as follows:

(a) Project activities may be bundled or portfolio bundled at the following

stages in the project cycle: the project design document, validation,

registration, monitoring, verification and certification. The size of the total

bundle should not exceed the limits set out for the three project types (i) to (iii)

above;

(b) The requirements for the project design document are reduced;

(c) Baseline methodologies by project category are simplified to reduce the cost

of developing a project baseline;

(d) Monitoring plans are simplified, including simplified monitoring

requirements, to reduce monitoring costs; and

(e) The same operational entity may undertake validation, and verification and

certification.

A simplified baseline and monitoring methodology listed in Appendix B of Annex

II to decision 21/CP.8 (FCCC/CP/2002/7/Add.3) may be used for a small-scale CDM

project activity if the project participants are able to demonstrate to a DOE

that the project activity would otherwise not be implemented due to the

existence of one or more of the following barriers:

(a) Investment barrier: a financially more viable alternative to the project

activity would have led to higher emissions;

(b) Technological barrier: a less technologically advanced alternative to the

project activity involves lower risks due to the performance uncertainty or low

market share of the new technology adopted for the project activity and so would

have led to higher emissions;

(c) Barrier due to prevailing practice: prevailing practice or existing

regulatory or policy requirements would have led to implementation of a

technology with higher emissions;

(d) Other barriers: without the project activity, for another specific reason

identified by the project participant, such as institutional barriers or limited

information, managerial resources, organizational capacity, financial resources,

or capacity to absorb new technologies, emissions would have been higher.

But these simplifying measures do not necessarily address the issues that

concern buyers and traders. It will probably be necessary for one developer to

aggregate projects so that sufficient CERs are on offer with adequate security

to draw the attention of market-actors. Otherwise, perhaps several developers

can find a secure way to act in a concerted entity.

A couple of examples of the scale of expectations for CER for various types of

projects are given in ANNEX B.

1.4 The market-value of CER

It is important to realise that (a) the market for Carbon credits is young

and thus illiquid at present; and (b) the rules and policies for trading in

carbon are slightly different in various markets, but that such differences are

likely to be ironed out over time. So, for example, whereas other states in the

EU-ETS have used a tonne of carbon dioxide (CO2) as the standard unit

of emissions of GHG, the UK has used carbon. And, whereas the EU-ETS refers only

to emissions of (CO2), the UNFCCC’s systems offer credits for

reductions in emissions of six GHG9.

Prices in European Trading Scheme (ETS)

Prices on the early trades of the EU ETS have reached values around 12-14 € in

the end of year 2003-beginning of 2004, then they have been between 7 and 10 €

in the second half of year 2004, but have increased substantially in 2005

(Figure 3, a) and overcome the value of 20 € in June 2005. However, as regards

recent prices, it can be said that they have been rather volatile in June and

July 2005 (Figure 3, b) , as the market is just starting to develop.

a)

b)

Figure 3: Prices of CO2 emissions in European Trading Scheme (ETS), €/t. a)

Period May 2003-March 2005; b) Period 25/05-20/07, year 2005. Source:

PointCarbon11

CER/ERU Prices

The most important early buyers of carbon-credits have been large

institutional bodies like the World Bank’s Prototype Carbon Fund (WBPCF) and

national governments, such as the Dutch Government’s Carboncredits.nl

Programme. According to publications of the CCPO (Climate Change Projects

Office, 2004), the WBPCF was offering about 3 Euros/tonne of CO2e

about a year ago, but was planning to introduce another scheme that would offer

a higher price for credits that demonstrate a high level of community benefits.

CCPO’s document also refers to a Dutch system that then offered a range of

values, from a maximum of about 3 Euros/tonne of CO2e for a project

entailing flaring methane at a landfill, to a maximum of about 5 Euros/tonne of

CO2e for projects generating electricity from renewable sources.

Current prices of flexible mechanisms certificates (CER and ERU) are, indeed,

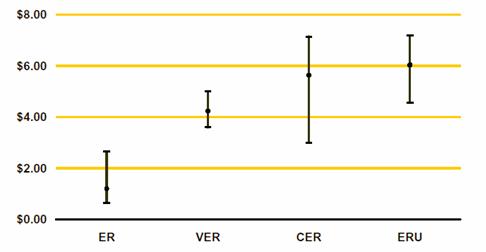

much lower than ETS certificates. Range of prices found for ERs, VERs, CERs12

and ERUs from January 2004 to April 2005, are reported in Figure 413.

Figure 4: average prices for non-retail project-based ERs (period january 2004-april 2005; in US $ per tCO2e). Source: IETA, 2005.

Most recent reports from Point Carbon (a major international carbon broker)

point to recent upward movement in the CER price — driven increasingly by demand

for them within the EU trading system. The June issue of the CDM & JI Monitor

reports CER offer prices in the 5 to 7 Euro range (for abatement certificates

from yet-to-be-registered CDM projects), and trades for registered CERs

occurring at above the 10 Euro mark14.

Prices depend on structure, vintage, creditworthiness of seller (sometimes also

buyer). CERs are created through the successful operation of an eligible

project. They are lower than EUA prices due to risks affecting the CER/ERU

creation (JI/ CDM eligibility, project performance risk and CER/ERU transfer

risks).

It can be pointed out here that risk of eligibility of CDM projects is reduced

as CDM EB has become operational and procedures clearer15.

Besides, transfer and delivery risk is also reduced for CDM as CDM registry is

being set up (first phase terminated)16.

How to trade ERUs, CERs, EUAs

Emission reductions certificates (ERUs, CERs, EUAs) can be traded by direct

or indirect contracting.

Direct contracting can be done in two manners: a) Bilateral, i.e. two companies

dealing directly (so that they have to be experienced counterparties) and b)

through Broker, i.e. over the counter. In the latter case, key factors are:

ability to achieve best price, access to large pool of buyers, expert advice on

how to structure transaction, tailored transactions, assistance with technical,

financial due-diligence, possibility to ensure anonymity, important if large

volumes need to be traded. Exchanges do not yet exist, as there is still the

necessity to develop clearing system and standardised contracts.

Indirect contracting is based on funds and financial institutions. This option

is particularly good for inexperienced buyers, but it is characterised by

inflexibility, as the client locks into a specific price for larger volumes.

Besides, the client has to check out capabilities, capital, creditworthiness and

track record of fund managers.

1.5 Use of CDM projects for compliance with EU ETS Directive – the Linking

Directive

The EU emissions trading scheme (ETS) is based on a recognition that

creating a price for carbon through the establishment of a liquid market for

emission reductions offers the most cost-effective way for EU Member States to

meet their Kyoto obligations (ANNEX D) and move towards the low-carbon

economy of the future.

The scheme is based on six fundamental principles:

- It is a ‘cap-and-trade’ system

- Its initial focus is on CO2 from big industrial emitters

- Implementation is taking place in phases, with periodic reviews and

opportunities for expansion to other gases and sectors;

- Allocation plans for emission allowances are decided periodically

- It includes a strong compliance framework

- The market is EU-wide but taps emission reduction opportunities in the rest of

the world through the use of CDM and JI, and provides for links with compatible

schemes in third countries.

As soon as a compromise on the ETS directive (2003/87/EC) was found, the

European Commission proposed an amending Directive, which will allow operators

in the ETS to use credits from the Kyoto Protocol project mechanisms - Joint

Implementation (JI) and the Clean Development Mechanism (CDM) - to meet their

targets in place of emission cuts within the EU.

The EU scheme is the first in the world that recognises most of these credits as

equivalent to emission allowances (1 EUA = 1 CER = 1ERU) and allows them to be

traded under the scheme17.

Nonetheless, the text of the Linking Directive finally adopted (2004/101/EC),

introduces some qualitative limitations: 1) credits from land-use change and

forestry (sinks) project are excluded for the period 2005-7 and their subsequent

introduction will be determined by a Commission review. 2) Hydroelectricity

projects are allowed, but it is required to take into account international

criteria such as those elaborated by the World Commission on DAMs, especially

for projects with a generation capacity of over 20 MW. 3) Credits from nuclear

power projects are excluded, which reiterates the language under the Kyoto

Protocol, which does not allow such projects to be counted as generating

emission reduction credits.

A quantitative limitation is also defined for the period 2008-2012: Member

States will have to specify (taking into account supplementarity requirement of

the Protocol) a limit up to which individual installations will be able to use

external credits to comply with the ETS, expressed in x% of initially allocated

allowances for that installation.

Companies are not the only ones looking for emission reduction credits through

JI and CDM. Member States intend to use such credits themselves to help meet

their emission target under the Protocol. As of October 2004, Member States had

provisionally indicated in their national allocation plans that they intend to

procure 500–600 million tonnes of CO2 credits for the period 2008–12. Since the

majority of JI and CDM projects tend to generate emission reductions averaging

between 500.000 and one million tonnes of CO2, EU countries' demand for emission

credits can only be satisfied through a great number of such projects. As 2008

draws nearer, EU Member States are actively seeking JI and CDM projects and a

number of project contracts have already been signed (see, e.g., 1.5.1).

With this strong demand for emission credits building up rapidly, major European

banks are becoming active in providing finance for prospective emission

reduction projects. At the end of 2003, the European Investment Bank created a

dedicated financing facility of € 500 million. Likewise, Germany’s European

banks are considering similar initiatives.

It is likely that strong driver for CER, ERU prices will be the demand from

governments and from EU, Canadian and Japanese companies.

In order to promote development of CDM projects, countries in Annex I are

signing Memoranda of Understanding (MoUs) with non-Annex I countries.

A MoU is a bilateral (non-binding) agreement between two countries, which is

intended to facilitate the processing of JI/CDM projects.

Agreements established by European Countries for CDM projects are reported in

ANNEX D.

In the next paragraphs, the CDM policies of countries that are possible buyers

of credits from Sri Lankan projects (i.e. The Netherlands and Italy) are

presented.

1.5.1 The case of The Netherlands and CDM

The Netherlands are one of the first countries which have earmarked public

funding for buying CO2 reductions by CDM. The Ministry of Housing,

Spatial Planning and the Environment (VROM) is responsible for the

implementation of CDM schemes.

The Dutch government has a substantial budget available for the implementation

of CDM. In April 2001, the Ministry of VROM set up a CDM Division as part of the

International Environmental Affairs Directorate of the Ministry. The

responsibility of the division is to use the funds allocated by the Dutch

government to purchase Certified Emission Reductions (CERs) from sustainable

projects in developing countries in a cost-effective manner.

The Ministry of VROM intents to purchase CERs through the following four tracks:

1. Multilateral international financial institutions;

2. SENTER International, a Dutch agency acting on behalf of several Dutch

Ministries;

3. Private financial institutions;

4. Bilateral purchase-agreements with Host Countries.

Via the above ways VROM is contracting various organizations to act as

intermediaries for the purchase of CERs. Under the guidance of VROM, these

intermediaries select sustainable projects in developing countries and purchase

the resulting CERs for the benefit of the Ministry. Investors from all countries

may submit CDM-project proposals to these intermediaries that will judge these

projects, including the compliance with the requirements.

Agreements with these intermediaries are described hereafter.

The World Bank18

announced an agreement with the Netherlands in May 2002, establishing a facility

to purchase greenhouse gas emission reduction credits. The Facility supports

projects in developing countries in exchange for such credits under the Clean

Development Mechanism (CDM) established by the Kyoto Protocol to the UN

Framework Convention on Climate Change (See ANNEX C)19.

Another new fund managed by the International Finance Corporation of the World

Bank Group on behalf of the Dutch Government is the IFC-Netherlands Carbon

Facility (InCAF). According to the IFC website InCAF is an arrangement under

which the IFC will purchase CERs for the benefit of the Government of The

Netherlands20.

The Netherlands will use these emission reductions to help meet its commitments

under the Kyoto Protocol. It has allocated € 44 million for InCAF to be used

over the next three years21.

Finally, within the context of establishing GHG opportunities on the buy and

sell side, Latin American Carbon Program, (PLAC in Spanish) is engaged in

diversifying the buyer pool of emission reductions which benefit CDM projects in

Latin America and the Caribbean. An example of these activities is the current

CAF-Netherlands CDM Facility or CNCF. The CAF-Netherlands CDM Facility focuses

on public and private sector transactions, located in countries in Latin America

and the Caribbean.

The Netherlands have already signed many contracts to buy emission credits from

CDM and JI projects. The CDM projects are reported in Table 1.

Table 1: Dutch CDM Projects

| PROJECT | CATEGORY | INVESTOR | LOCATION |

| Columbo Bagasse cogeneration project | Energy Efficiency | Brazil | |

| Fortuna hydroelectric project | Large Hydro | CERUPT | Panama |

| Huitengxile wind project | Renewables | CERUPT | China |

| Onyx landfill gas project | Gas Capture or destruction | CERUPT | Brazil |

| Kalpataru biomass plant project | Renewables | CERUPT | India |

| Rio Azul landfill gas capture project | Gas Capture or destruction | CERUPT | Costa Rica |

| V&M do avoided fuel switch project | Fuel Switching, Gas Capture or destruction | IFC-Netherlands Carbon Facility (INCaF) | Brazil |

| NovaGerar landfill gas project Gas Capture or destruction | Netherlands CDM Facility | Brazil | |

| Gujarat HFC23 decomposition project | Gas Capture or destruction | RaboBank | India |

| Haidergarh bagasse co-generation project | Renewables | IFC-Netherlands Carbon Facility (INCaF) | India |

| TransMilenio urban transport project | Transport | CAF-Netherlands CDM Facility | Colombia |

| Vinasse anerobic treament project | Gas Capture or destruction, Renewables | CAF-Netherlands CDM Facility | Nicaragua |

| Poechos hydroelectric project | Large Hydro | Netherlands CDM Facility | Peru |

| Matuail landfill gas project | Gas Capture or destruction, Renewables | World Wide Recycling (Netherlands) | Bangladesh |

| Villa Dominico landfill gas project | Gas Capture or destruction | Van der Wiel Stortgas | Argentina |

| Santa Cruz landfill gas project | Gas Capture or destruction | Grontmij Climate & Energy | Bolivia |

| Anding landfill gas project | Gas Capture or destruction | Energy Systems International BV | China |

| Matuail landfill organic waste composting project | Gas Capture or destruction, Renewables | World Wide Recycling (Netherlands) | Bangladesh |

| Shri Bajrang waste heat recovery project | Energy Efficiency | BHP Billiton International Metals BV | India |

1.5.2 The case of Italy and CDM

In Italy, project-based carbon credits are expected to offset national

emissions reduction of the first CP between 10% and 50%. So, flexible mechanisms

will complement Italian internal policies, on account of their greater

convenience in terms of the unit cost for reducing emissions.

Flexible mechanisms will contribute to the overall foreseen reduction through

activities sponsored by public institutions and activities carried out by

private companies.

The exact extent, to which flexible mechanisms will contribute, will depend on

the evolution of both the carbon market as well as national abatement costs.

Table 2: Emissions scenarios and reduction target for period 2008-2012 (Mt di

CO2).

|

"Business as usual" scenario |

"Reference" scenario (measures already approved or established) |

Emissions target (Kyoto protocol) |

Further reduction necessary to reach emissions target |

| 579,9 | 528,1 | 487,1 | 41,1 |

| FROM ENERGY SOURCES | 444.5 | |

| Energy industries, of which: | 144.4 | -26 |

|

- thermoelectric |

124.1 |

|

|

- refinery (direct consumptions) |

19.2 |

|

|

- others |

1.1 |

|

| Manufacturing and construction industries | 80.2 | |

| Transportation | 134.7 | -7,5 |

| Residential and tertiary | 68 | -6,3 |

| Agriculture | 9.6 | |

| Others (fugitives, military, distribution) | 7.6 | |

| FROM OTHER SOURCES | 95.6 | |

| Industrial processes (mineral and chemical industries) | 30.4 | |

| Agriculture | 41 | |

| Waste | 7.5 | |

| Others (solvents,fluorinated) | 16.7 | |

| CARBON CREDITS FROM JI AND CDM | -12 | -12 |

| TOTAL | 528.1 | -51,8 |

Considering that target for Italy for period 2008-2012 is 487,1 Mt of CO2

emissions, it is necessary to identify policies and measures for a further

reduction of 41 Mt CO2 (Table 2). To achieve this result, Italian Plan

specifies two broad options of additional measures: national reduction measures

and international flexible mechanisms, as reported in Table 322.

Table 3: Options for the adoption of additional emission reduction measures.

|

Potential reduction (Mt CO2 eq /year) |

|

| A) ADOPTION OF ADDITIONAL NATIONAL REDUCTION MEASURES | 30,4-44,2 |

| Use of energy sources |

22,3-35,4 |

|

Industrial sector |

5,1-9,6 |

|

Renewable sources |

1,8-3,4 |

|

Residential and tertiary sector |

3,8-6,5 |

|

Agricultural sector |

0,28-0,34 |

|

Transport sector |

11,3-15,6 |

| From other sources |

8,15-8,80 |

| B) USE OF THE JI AND CDM MECHANISMS | 20,5-48 |

| Carbon removal |

5-10 |

|

JI projects |

2-5 |

|

CDM projects |

3-5 |

| Projects in the energy sector |

15,5-38 |

|

JI Project to improve the efficiency of electricity generation and industrial activities |

3-10 |

|

CDM projects for the production of energy from renewable sources |

1-5 |

|

CDM projects to improve the efficiency of electricity generation and industrial activities |

1.5-3 |

|

JI and CDM gas-flaring and gas-venting projects in oil wells |

10-20 |

It can be noticed that the entire gap to reach the final target could be covered

by means of flexible mechanisms.

Italy has so far signed Memoranda of Understanding with several countries (see

ANNEX D). Furthermore, Italy enhanced international cooperation

programmes with the Balkans and Southern Mediterranean countries through the

MEDREP initiative23.

In order to explore the potentials of investment in credit generating mechanisms

Italy has a) signed an agreement to contribute US$7.7 million to the World

Bank's Community Development Carbon Fund (CDCF). The Fund supports small-scale

projects in the least developed countries (LDC) and poor communities in

developing countries which generate GHG emissions reductions; b) signed an

agreement to contribute US$2.5 million to the World Bank's BioCarbon Fund. The

Fund supports afforestation and reforestation projects; c) set up the Italian

Carbon Fund with the World Bank for GHG emissions reductions.

The BioCarbon Fund will provide carbon finance for projects that sequester or

conserve greenhouse gases in forests, agro- and other ecosystems. It is designed

to ensure that developing countries, including some of the poorest countries,

have an opportunity to benefit from carbon finance in forestry, agriculture and

land management. The Fund will help reduce poverty while reducing greenhouse

gases in the atmosphere24.

Italian Carbon Fund (created in agreement by the World Bank and the Ministry for

the Environment and Territory of Italy) is a fund to purchase greenhouse gas

emission reductions from projects in developing countries and countries with

economies in transition that may be recognized under such mechanisms as the

Kyoto Protocol’s CDM and JI25.

1.6 CDM projects in Sri Lanka26

Sri Lankan project developers are currently proposing 19 CDM projects, which

are in different states of the design/validation process. These projects are

mainly based on the introduction of renewable/alternative energies (hydro,

biomass and landfill gas) and of forestry initiatives.

Table 4: Sri Lanka

CDM Projects

|

PROJECT |

CATEGORY |

Investor for Carbon Credits |

STATE |

|

Projects for which carbon credits have already been sold |

|||

|

PV panels (how many planned?) |

Solar photovoltaic |

GEF/World Bank 1 |

10.000 Panels installed |

|

Minihydro, 15 grid-connected projects? |

|

GEF/World Bank |

Some built |

|

8 MW biomass |

|

GEF/World Bank |

Not built |

|

Projects for which carbon credits buyers are being sought (if buyers are not found World Bank will buy carbon credits at minimum price?) |

|||

|

1 MW Biomass Power Plant, Walapane |

Biomass |

|

PDD |

|

Delta, Halgran Oya, Sanquhar power project |

Hydro |

|

PIN |

|

1 MW Biomass Power Plant of Informatics Agrotech |

Biomass |

|

PDD |

|

Aqua Power (Pvt) Ltd – Labuwawa Mini Hydropower project |

Hydro |

|

PIN |

|

Tokyo Cement Biomass Power Project, Trincomalee |

Biomass |

|

PIN |

|

SJL Holdings (Pvt) Ltd |

Hydro |

|

PIN |

|

Coconut shell carbonising gas based power generation |

Biomass |

Japanese Fund ? |

PIN |

|

Rubber cultivation for Sustainable Development Forestry |

Forestry |

|

PIN |

|

Assupiniella Small Hydro Power Project |

Hydro |

|

PIN |

|

Vanasaviya Biodiesel Production |

Biomass/Biofuels |

|

PIN |

|

Biomass Power Project at Amapara |

Biomass |

Dutch Fund – PREGA 2 ? |

PIN |

|

SJL Minihydro (Pvt) Ltd |

Hydro |

|

PIN |

|

Adavikanda Small Hydro Power Project |

Hydro |

|

N.A. |

|

Barcaple Small Hydro Power Project |

Hydro |

|

N.A. |

|

Erathna Small Hydro Power Project |

Hydro |

|

N.A. |

|

Way Ganga Small Hydro Power Project |

Hydro |

|

N.A. |

|

Landfill Gas Energy Project |

Gas capture for energy recovery |

|

N.A. |

|

Sri Lanka Tsunami affected Mangrove forest rehabilitation project |

Forestry |

BioCarbon Fund? |

PIN |

1GEF is a

partnership among UNDP, UNEP and the World Bank. It operates as a

mechanism for providing new and additional grant and concessional funding to

meet the agreed incremental costs of measures to achieve agreed global

environmental benefits in the four focal areas - Climate change; Biological

diversity; International waters; and Ozone layer depletion (in 2001, Persistent

Organic Pollutants (POPs) program was also added in the GEF).

2 The Asian Development Bank (ADB) is administering the Dutch funded

Promotion of Renewable Energy, Energy Efficiency and Greenhouse Gas Abatement

- PREGA - program which will help will carry out pre-feasibility studies of

investment projects for financing consideration through commercial, multilateral,

and bilateral sources, including specialized treaty-linked mechanisms such as

the Global Environment Facility and the Clean Development Mechanism. It is being

implemented in the following developing countries: Bangladesh, Cambodia, China,

India, Indonesia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyz Republic, Mongolia, Nepal, Pakistan,

Philippines, Samoa, Sri Lanka, Uzbekistan, Vietnam.

Biomass potential for CDM projects

Figures of biomass availability for year 1997, obtained from the Sri Lanka

Energy Balance, are presented in Table 5.

Table 5: Biomass availability in Sri Lanka (year 1997).

| Type | Metric Tons / Year | % |

| Rice Husk available from commercial mills | 179,149 | 6.2 |

| Biomass from Coconut (plantations available for industrial use) | 1,062,385 | 37 |

| Sugar Bagasse | 283,604 | 8.3 |

| Bio degradable garbage | 786,840 | 27.4 |

| Saw Dust | 52,298 | 1.8 |

| Off cuts from Timber Mills | 47,938 | 1.7 |

| Biomass from Home Gardens such as Gliricidia | 505,880 | 17.6 |

| Total | 2,873,880 | 100 |

However, according to Biomass Energy Association of Sri Lanka (BEASL), there is

a potential for using scrub lands all over Sri Lanka to support the growing of

fuel wood species (Figure 5).

|

|

Figure 5: Land availability for dendro plantations in Sri Lanka.

Recent estimates show that available scrub lands add up to more than 1.6 million

hectares. These energy plantations would lead to about 48 million tons per year

of fuel wood27.

Accordingly, theoretic potential for installed power fuelled from short rotation

coppicing could reach 4.000 electric MW.

Short term potential is, however, estimated in 50-80 MWe, which correspond to

about 250-450,000 tons of CO2 emissions avoided.

Besides, in the long term, at least 10 clusters of biomass power plants of 100

MWe each are estimated as feasible. In this sense a possible figure for

biomass-generated carbon credits over the next ten years is 7 millions of tons

of CO2, consisting of:

- 5 million tons for power generation;

- 1 million tons for industry;

- 1 million tons for forestry sequestration.

According to first pre-feasibility studies28,

economic incremental abatement cost of CO2 for biomass projects could

be around 3-4 $ / ton, while financial (incremental abatement) cost could reach

values of 25-30 $ / ton.

Bibliography

CDM

CLIMATE CHANGE PROJECTS OFFICE, 2004. Several brochures: (a) A business

guide to climate-change projects; (b) The Joint Implementation and Clean

Development Mechanisms Explained; and (c) A beginner’s guide to the Clean

Development Mechanism.

Conference of Parties, Framework Convention on Climate Change, 2002. Decision

21/CP.8 Guidance to the Executive Board of the clean development mechanism (FCCC/CP/2002/7/Add.3).

7th plenary meeting 1 November 2002.

http://cdm.unfccc.int/Reference/Documents/guidance_to_EB/English/7add3.pdf

Ecosecurities Ltd, 2002. Moving towards Emissions Neutral Development (MEND)

- Final Technical Report. Oxford, September.

European Union (EU), 2002. COUNCIL DECISION of 25 April 2002 concerning the

approval, on behalf of the European Community, of the Kyoto Protocol to the

United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change and the joint fulfilment

of commitments thereunder (2002/358/CE). Brussels, April 25th.

European Union (EU), 2003. DIRECTIVE 2003/87/EC OF THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT

AND OF THE COUNCIL of 13 October 2003 establishing a scheme for greenhouse gas

emission allowance trading within the Community and amending Council Directive

96/61/EC. Brussels, October 13th.

European Union (EU), 2004. DIRECTIVE 2004/101/EC OF THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT

AND OF THE COUNCIL of 27 October 2004 amending Directive 2003/87/EC establishing

a scheme for greenhouse gas emission allowance trading within the Community, in

respect of the Kyoto Protocol’s project mechanisms. Brussels, October 27th.

IETA, 2005. State and Trends of Carbon Market 2005, Washington DC , May.

UNFCCC, CDM Executive Board, 2004. Tool for the demonstration and assessment

of additionality. Sixteenth meeting (EB 16), Bonn, 21-22 October 2004.

http://cdm.unfccc.int/methodologies/PAmethodologies/AdditionalityTools/Additionality_tool.pdf

http://www.climatetech.net/publications/

Abbreviations.

The subject of this report is derived from newly implemented legal processes

that have introduced new terms that are constructed from ordinary words, but

which have special meanings. These terms are often referred to by the following

abbreviations (which are used herein for both the singular and plural forms of

the terms):

CCL - the UK’s Climate Change Levy.

CCPO = the UK Government’s Climate Change Projects Office.

CDM = the Clean Development Mechanism – a means within the KM to

include those developing countries that are listed in Annex 2 of the Kyoto

Protocol in the drive to reduce emissions of GHG.

CER = Certified Emission Reductions - verified credits granted to validated

projects that can be sold on the carbon-market that can provide an extra

income-stream for eligible projects in developing countries.

CO2e = Carbon Dioxide Equivalent – the effect of six GHG

on global warming expressed in terms of their equivalence in this respect to

carbon dioxide..

DOE = Designated Operational Entity – a body that has been approved by

UNFCCC to validate a PDD, and/or to verify CER.

For any particular project, separate DOE are required for these two functions.

EB = Executive Board – the arm of UNFCCC that deals with CDM.

EU-ETS = the European Union’s Emissions Trading Scheme.

GHG = the so-called “Greenhouse gases”, which are a cause of global warming. The

UNFCCC’s systems cover six GHG, which are measured, for the

purposes of the CDM, in units of CO2e.

IET = International Emissions Trading - a system to give market-value to

CER, etc.

JI = Joint Implementation – a KM similar to CDM, but

applicable to countries listed in Annex 1 of the Kyoto Protocol.

KM = Kyoto Mechanisms.

PDD = Project Design Document – a description of the proposed project that

starts the legally secure process towards gaining CER.

UNFCCC - the United Nations’ Framework Convention on Climate Change.

WBPCF – the World Bank’s Prototype Carbon Fund.

2 ANNEXES

2.1 ANNEX A: Methodologies approved by CDM Executive Board (EB)

Approved methodologies can be found at UNFCCC/CDM site: http://cdm.unfccc.int/methodologies/PAmethodologies/approved.html.

The methodologies are continuously revised and updated.

Approved methodologies for small-scale projects can be found at: http://cdm.unfccc.int/methodologies/SSCmethodologies/approved.html

The additionality of the project activity shall be demonstrated and assessed

using the

![]() Tool for the demonstration and assessment of additionality.

Tool for the demonstration and assessment of additionality.

Graphic overview of procedures for submission and consideration of proposed new

methodologies can be found at:

http://cdm.unfccc.int/Projects/pac/howto/CDMProjectActivity/NewMethodology/graphmeth.pdf

2.2 ANNEX B: Examples of projects

Example 1. Using landfill-gas at a large landfill site.

Consider a landfill that contains about 1 million tonnes of mixed wastes

that have been deposited within the past ten years, and is emitting substantial

amounts of landfill gas (LFG) which, in the baseline case, is not controlled in

any way. As a rule of thumb (which has to be checked by on-site pumping trials,

etc.), there might be enough gas - say 600 Nm3/hour of LFG consisting

of 50 per cent by volume of each of CH4 and CO2 – to run a generating set rated

at 1 MWe. If that set is run for 8,000 hours/year, it will destroy 300 x 8,000 =

2.4 million Nm3/year of CH4.

The density of methane at 0 oC and 1 bar is 0.717 kg/m3, so the

annual mass of 2.4 million Nm3/year of CH4 is about 1,720

tonnes which (in terms of effects on climate-change) is taken to be (using the

factor of 21 – see above) equivalent to about 36,000 tonnes of CO2.

In practice, the amount of CH4 destroyed is likely to be larger

because, to secure sufficient LFG for the generator(s), and over-sized

gas-collection system would be installed because the output of LFG varies for

several reasons. It is good practice to flare the excess LFG from such a system.

It may be necessary to collect all of the LFG from the site for safety reasons,

in which case even more LFG will have to be flared.

The treatment of this example will vary depending on the location of the site.

Within the EU, the Landfill Directive requires the proper treatment of LFG,

including drainage and high-grade flaring as necessary, and so, as that is a

legal requirement anyway, a developer installing the necessary equipment could

not expect attract credits under the JI. But that developer could expect credits

in a JI from the displacement of electricity made from fossil fuels with

electricity generated from LFG.

In contrast, in a developing country, there may be no such regulations, in which

case, the develop would seek to receive credits under the CDM for both (a) the

drainage and destruction of all of the treated methane (including that burnt in

the generation of power), and (b) the displacement of electricity made from

fossil fuels with electricity generated from LFG.

The exact basis for calculating CER has to take account of the particular

circumstances offered by the project. For example, a typical power station

burning hard coal emits about 0.80 tonnes of CO2 for each MWeh

it generates, whereas the use of brown coal increases this to about 1.0 tonne of

CO2/MWeh. And a generator running on diesel-oil also emits

about 1.0 tonne of CO2/MWeh, while a power station fired with natural gas and

using a combined-cycle gas-turbine emits only about 0.45 to 0.50 tonnes of CO2/MWeh,

because of the better properties of the fuel and the more efficient process.

Example 2. Replacing coal with biomass at a power-station.

Consider as a baseline case a power station fuelled with coal that has a

rated output of 30 MWe, which operates at a conversion-efficiency of

33 per cent, and is run for 7,000 hours/year.

The properties of coal vary greatly. A medium-grade coal might have a gross

energy-content of about 22 GJ/tonne (or about 6 MWh), and burning 1 tonne of

that coal will produce about 2 tonnes of CO2. If that coal is burned in a power

station having a conversion-efficiency of 38 per cent, there will be about 0.9

tonnes of CO2 emitted for each 1 MWeh generated.

A developer might look at replacing the coal-burning power station completely

with one that burns biomass of various kinds, or alternatively consider keeping

the existing station but replacing some of the coal with wood in a so-called “co-firing”

project, interest in which has grown rapidly within the UK over the past three

years. The potential for producing CER is easy to visualise in both of these

options.

2.3 ANNEX C: Netherlands CDM Facility – Project Selection Criteria

Projects shall be selected in accordance with the following Project

Selection Criteria:

(a) Consistency with United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC)

and/or the Kyoto Protocol. Projects should comply with all current decisions

on modalities and procedures adopted by the Parties to the UNFCCC and/or the

Kyoto Protocol, as well as all future decisions on modalities and procedures,

when adopted, in particular those pertaining to sustainable development and

additionality.

(b) Consistency with Relevant National Criteria. Project designs should

be compatible with and supportive of the national environment and development

priorities of the Host Countries. In addition, the projects, the transfer of

Emission Reductions (ERs) and the issuance of Certified Emission Reductions (CERs)

should be consistent with the rules and criteria adopted by Host Countries

regarding Clean Development Mechanism (CDM) projects.

(c) Consistency with the General Guidance Provided by VROM . Projects

should comply with the VROM requirements and the general guidance provided by

VROM at their regular meetings. (VROM is the State of the Netherlands, acting

through the Ministry of Housing, Spatial Planning and the Environment.)

(d) Location of Projects. Projects should be located in Non-Annex I

Countries which have (i) signed and ratified, accepted, approved or acceded to

the Kyoto Protocol, or (ii) signed the Kyoto Protocol and demonstrated a clear

interest in becoming a party thereto in due time, for example those that have

already started or are on the verge of starting their national ratification,

acceptance or approval process or (iii) already started or are at the verge of

starting the national accession process.

(e) No Nuclear Energy. Nuclear energy projects are not eligible.

(f) LULUCF (Land-Use, Land_Use Change and Forestry). Projects involving

land-use or land-use change (afforestation, reforestation) are only eligible

after the COP/MOP has decided on the relevant modalities and guidelines and VROM

has agreed to accept such projects.

(g) Environmental and Social Impacts. Projects that are expected to have

large scale adverse social or environmental effects are not eligible.

(h) Advance Payments. Projects that will require Advance Payments from

the NCDMF, shall not be eligible, unless at least 50% (fifty percent) of the

total financing needs of such Project will be provided by other entities which

are at least A+ rated by S&P or A1 rated by Moody's (bank rating or debt paper

rating).

(i) Purchase Price. Projects that involve a purchase price of more than €

5.5 (five and a half Euros) per metric tonne of CO2 equivalent, calculated on

the basis of ER Unit Price and the Kyoto Protocol Related Project Costs, shall

not be eligible, unless they are expected, in VROM's opinion, to make a very

significant contribution to sustainable development in the Host Country,

preferably in Least Developed Countries.

(j) Proportion of Payments. The present value of the total payments (calculated

at a discount rate of no more than 4% (four percent) to be made by the NCDMF for

the purchase of ERs, shall not exceed 30% (thirty percent) of total financing

needs of the project at commissioning, unless otherwise agreed by VROM.

(k) Financing of Projects. Of the total financing needs of each

individual project at least 30% (thirty percent) shall be covered by

co-investing entities meeting at least a rating of A+ by S&P or A1 by Moody's (bank

rating or debt paper entities). If such is not the case, an extensive due

diligence performed by the NCDMF may determine the project's eligibility.

(l) Complementarity with GEF(Global Environment Facility). Projects

should be complementary to the GEF and not compete with the GEF's long-term

operational program nor with their short-term response measures. In furtherance

of this criterion, potential projects will be reviewed by the Secretariat of the

GEF to determine their GEF eligibility. Only if it is determined that a

potential project will not receive GEF financing will it be considered for

inclusion as a NCDMF project.

(m) Complementarity with the PCF (Prototype Carbon Fund). The PCF shall

have the right of first refusal of a Project.

(n) Cost-effectiveness and Sustainability. Cost-effectiveness and

sustainability will play a major role in selection and approval of projects.

Projects may be drawn from a broad range of technologies and processes in energy,

industry, and transport, which provide various vehicles for generating ERs,

which contribute to sustainable development and achieve transfer of cleaner and

more efficient technology to Host Countries. VROM ranks technologies in the

following descending order: (i) renewable energy technology, such as geothermal,

wind, solar, and small-scale hydro-power; (ii) clean, sustainably grown biomass

(no waste); (iii) energy efficiency improvement; (iv) fossil fuel switch and

methane recovery; (v) sequestration. VROM expects this ranking to be reflected

in the ER Unit Price.

(p) Additional Characteristics of Projects. Projects should generally

entail manageable technological risk. The technology to be used in a project

should be commercially available, have been demonstrated in a commercial context,

and be subject to customary commercial performance guarantees. The technical

competence in the Host Country to manage this technology should be established

in the course of Project appraisal. Projected Emission Reductions over the life

of the Project should be predictable and should involve an acceptable level of

uncertainty.

2.4 ANNEX D: EU CO2 emissions reduction targets and CDM programmes

Emission allocations and number of installations covered by the EU emissions

trading scheme per Member State (indicative table based on national allocation

plans approved) and their Kyoto emission targets.

| Member State | CO2 allowances in million tonnes | Installations covered | Kyoto target |

| Austria | 99.01 | 205 | –13 %(*) |

| Belgium | 188.8 | 363 | –7.5 %(*) |

| Czech Republic | 292.8 | 436 | –8 % |

| Cyprus | 16.98 | 13 | - |

| Denmark | 100.5 | 362 | –21 %(*) |

| Estonia | 56.85 | 43 | –8 % |

| Finland | 136.5 | 535 | 0 %(*) |

| France | 469.53 | 1172 | 0 %(*) |

| Germany | 1497.0 | 2419 | –21 %(*) |

| Greece | 223.3 | 141 | +25 %(*) |

| Hungary | 93.8 | 261 | –6 % |

| Ireland | 67.0 | 143 | +13 %(*) |

| Italy | 697.5 | 1240 | –6.5 %(*) |

| Latvia | 13.7 | 95 | –8 % |

| Lithuania | 36.8 | 93 | –8 % |

| Luxembourg | 10.07 | 19 | –28 %(*) |

| Malta | 8.83 | 2 | - |

| Netherlands | 285.9 | 333 | –6 %(*) |

| Poland | 717.3 | 1166 | –6 % |

| Portugal | 114.5 | 239 | +27 %(*) |

| Slovak Republic | 91.5 | 209 | –8 % |

| Slovenia | 26.3 | 98 | –8 % |

| Spain (**) | 523.7 | 927 | +15 % |

| Sweden | 68.7 | 499 | +4 %(*) |

| United Kingdom (***) | 736.0 | 1078 | –12.5 %(*) |

| Total so far | 4 641.97(**) | 9089(**) | |

|

Approximate percentage of estimated overall total |

ca. 70 % |

ca. 70 % |

|

(*) Under the Kyoto Protocol, the EU-15 (until 30 April 2004 the EU had 15

Member States) has to reduce its greenhouse gas emissions by 8 % below 1990

levels during 2008–12. This target is shared among the 15 Member States under a

legally binding burden-sharing agreement (Council Decision 2002/358/EC of 25

April 2002). The 10 Member States that joined the EU on 1 May 2004 have

individual targets under the Kyoto Protocol with the exception of Cyprus and

Malta, which as yet have no targets.

(**) Figures do not include some Spanish installations for which allocations are

in preparation.

(***) Latter revised plan, which had an increase of emission allocations, has

been rejected.

Agreements established by EU 25 Member States for CDM/JI projects are presented

hereafter.

|

MEMBER STATE |

AGREEMENTS FOR CDM PROJECTS |

|

Austria |

Information on the

Austrian CDM/JI program is available at

http://www.ji-cdm-austria.at/en/downloads.php Carbon Fund (CDCF) |

|

Belgium |

Belgium-Wallonia and the Brussels Region are investors in the World Bank's Community Development Carbon Fund (CDCF) |

|

Czech Republic* |

|

|

Cyprus** |

Cyprus has a CDM MoU with Italy |

|

Denmark |

EcoSecurities and

Standard Bank London Ltd are managing the Denmark Carbon Facility

for the Danish Government |

|

Estonia* |

|

|

Finland |

Finland has a CDM MoU

with Costa Rica, El Salvador and Nicaragua, and CDM co-operation is

included in general agreements with India and China |

|

France |

France has CDM

MoUs with Colombia, Morocco, Argentina and Chile |

|

Germany |

Germany has funded

a

study assessing the feasibility of a project to improve

energy efficiency in industrial boilers in Peru |

|

Greece |

|

|

Hungary* |

|

|

Ireland |

|

|

Italy |

Italy has signed MoUs

with China, Serbia, Moldova, Croatia, Bulgaria, Poland, Slovenia,

Morocco, Argentina, Egypt, Algeria, Cyprus, Israel, Cuba, El

Salvador. Letters of Intent exist with Brazil and Romania |

|

Latvia* |

|

|

Lithuania* |

|

|

Luxembourg |

Luxembourg is an investor in the World Bank's BioCarbon Fund (BCF) and Community Development Carbon Fund (CDCF) |

|

Malta |

|

|

Netherlands |

Rabobank |

|

Poland* |

|

|

Portugal |

|

|

Slovak Republic* |

|

|

Slovenia* |

|

|

Spain |

Spain has invested Euro 200 million in a range of World Bank carbon funds. Euro170 million will finance a Bank-managed Spanish Carbon Fund; Euro20 million will be invested in the CDCF; Euro10 million will be invested in the BCF; Euro5 million will be invested in the Bank's CF Assist program Spain has a CDM MoU with Panama, Argentina and Brazil |

|

Sweden |

Survey of CDM initiatives and potential technology

collaboration between China and Sweden - the case of biomass energy

technology |

| United Kingdom |

A study on the

CDM in Kenya with a particular focus on opportunities for UK

business EcoSecurities will soon be carrying out an activity in India focussing on industrial CDM potential. The project is being supported by the UK's Foreign and Commonwealth Office and British High Commission, India The UK and European Commission are jointly funding the CDM Susac program which aims to promote the CDM in Africa, the Carribean and Pacific countries. It is coordinated by the IER University of Stuttgart (Germany) and has partners in Senegal, Uganda, UK and Zambia The British Government conducted a study on CDM projects titled "Initial evaluation of CDM type projects in developing countries". The reports can be found at http://www.surrey.ac.uk/eng/ces/research/ji/cdm-dfid.htm The UK Department for International Development (DfID) funded a project coordinated by Ecosecurities to examine the developmental potential of the CDM; to investigate strategies to encourage CDM investment flows in small to medium developing countries; and to suggest ways that donors could get involved in capacity building to facilitate the participation of these developing countries in the CDM. The project had four developing country partners - Bangladesh, Colombia, Ghana and Sri Lanka - for which country papers are available |

| Canada |

The Canadian

Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAIT) and the Canadian

International Development Agency (CIDA) with the Pembina Institute

for Appropriate Development (PIAD) established the Canadian Clean

Development Mechanism Small Projects Facility (CDM SPF) in 2002. A

summary of projects in India is available

here Canada has CDM MoUs with Costa Rica, Argentina, Colombia, Chile, Nicaragua, Tunisia, Sri Lanka, Bolivia and South Korea Canada is an investor in the World Bank's Community Development Carbon Fund (CDCF), BioCarbon Fund (BCF) and Prototype Carbon Fund (PCF). The Asian Development Bank (AD) is administering the US$5M Canadian Cooperation Fund on Climate Change The Pembina Institute in Canada and Tata Energy Research Institute (TERI) in India are exploring the application of the Clean Development Mechanism (CDM) in Asia, funded by the Canadian International Development Agency. For more information and to download reports go to www.pembina.org/international_eco3a.asp or www.teriin.org |

| Japan |

The Institute for

Sustainable Energy Policies, Japan, has written an

overview

of Japanese CDM activities The Japanese Government has conducted a number of feasibility studies for CDM and JI projects The New Energy Development Organisation (NEDO) of METI is conducting a range of feasibility studies. Brief summaries are on their website Japan is an investor in the PCF |

* EIT (Economy in transition): countries that are undergoing the process of

transition to a market economy.

** Non-ANNEX I Party: countries classified as least developed countries (LDCs)

by the United Nations.

________________________

* Paper for the conference "issues for the

sustainable use of biomass resources for energy", Colombo, 15-19th august 2005.

ASIA PRO-ECO PROJECT "The way forward for the use of wood and agricultural waste

for energy production in S.E. Asia".

◊ Prof. Engineer,

Director of the Department of Applied Sciences to Complex Systems of the

Technical University of Marche (Italy).

♦Engineer, Italian

Thermo-technical Committee (CTI) - Research Sector. E-mail: alberti@cti2000.it.

1 These gases are hereinafter called Greenhouse Gases (GHG)

because of their so-called Greenhouse Effect on climate-change.

2 For example, there is a great disparity between developed and

developing countries in the amounts per capita of fossil fuels used and GHG

emitted.

3 United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change -

Convention-cadre des Nations Unies sur les changements climatiques

4 A format for the PDD, and guidance for its drafting, can be

down-loaded from the UNFCCC’s Web-site at: http://cdm.unfccc.int/Reference/Documents.

5 Further information on the process of validation and on DOE is

available on the UNFCCC’s Web-site at: http://cdm.unfccc.int/Reference/Procedures

and: http://cdm.unfccc.int/DOE. A list of DOEs can be found on: http://cdm.unfccc.int/DOE/list.

6 COP 7, Marrakech, Morocco, November 2001.

7 It may be the case, at least in the first compliance period

(2008 - 2012), that the CDM market is limited, and that larger projects could 'crowd'

out the smaller projects, due to the comparatively higher price of the emission

reductions generated by small-scale projects.

8 On contrary, the load factor which would affect the real

output is not taken into consideration.

9 To take account of their effects on climate-change relative to

the influence of CO2, factors are applied to the other five GHG, and the

totality is then expressed as “equivalent carbon dioxide” (CO2e). For example,

one powerful GHG is methane (CH4), which is taken to have, volume for volume, 21

times more intensive effects on global warming than CO2.

10 In the UK, the Government’s Department of the Environment,

Food and Rural Affairs has estimated that the real cost of emissions of fossil

carbon is about £70/tonne (i.e. about 28 Euros/tonne of CO2), but the existing

relevant environmental tax on electricity in the UK – the Climate Change Levy (CCL)

– has been set at £4.30/MWeh, which is equivalent to £37/tonne of carbon, and

thus to about 15 Euros/tonne of CO2. Incidentally, the CCL is not levied on

residential users, who consume a very large quantity of fossil fuels for heating,

etc. Furthermore, although it is levied on industrial companies, they can

achieve large reductions in their tax-bills by engaging in approved programmes

for promoting energy-efficiency, etc.

11 Point Carbon’s volume-weighted assessment is based on

over-the-counter (OTC), brokered trades. Every day, active brokers in the EU

emissions trading scheme volunteer to supply their market information at close

of market to Point Carbon. Each broker acts with the permission of their

management. The brokerages act independently from each other and the information

they provide is confidential and held by Point Carbon. The data is not

circulated outside Point Carbon and is used solely for compiling the market

assessment. The price refers to one EU allowance, equivalent to one metric tonne

of carbon dioxide emissions. Adopted methodologies are Volume-weighted

methodology or Bid-offer close methodology.

12 CER = a unit of GHG reductions that has been generated and

certified under the provisions of the Kyoto Protocol for Clean Development

Mechanisms (CDM); VER = a unit of GHG reductions that is verified (by third

parties) and traded outside of Kyoto compliant mechanisms. ER = a unit of

non-verified/certified GHG reductions.

13 The best way to determine such values is to open discussions

with potential buyers and traders who are interested in this market. Initial

soundings suggest, for planning purposes, a prospective value of about 6 Euros/tonne

of CO2e for suitable projects. At least two key issues arise in the

consideration of what will constitute “suitable projects” for this purpose:

potential buyers and traders will be seeking projects that are (a) large -

generating more than, say, 50,000 CER/year; and (b) secure – their

counter-parties will have to achieve high levels of credit-rating.

14 Point Carbon (2005), CDM Market Comment, CDM & JI Monitor,

14 June 2005 (p.2). www.pointcarbon.com.

15 On the contrary, JI Supervisory Committe is to be elected by

COP/MOP 1 (The Conference of the Parties serving as the Meeting of the Parties),

to be held in November/December 2005, together with COP 11.

16 On the contrary, for ERU, host country transfer risk is

increased due to commitment period reserve (90% of AAUs or latest 100% of latest

inventory).

17 Import of CERs is permitted from 2005, ERUs from 2008

18 International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD).

19 The Facility’s initial target was to purchase 16 million

tons of carbon dioxide equivalent (mtCO2e) in the first two years of the

agreement. The agreement has now been extended, with a firm commitment to

purchase an additional five mtCO2e by mid-2005. The agreement also allows for a

further purchase of up to approximately 11 million tons of carbon dioxide

equivalent.

20 InCAF is looking for projects with the following

characteristics:

- Location: projects can be located in most developing countries. Projects in

newly industrializing countries in Central and Eastern Europe are not eligible.

A list of eligible countries is available on request.

- Likely project closing: projects must be likely to reach financial closing

within the short term.

- IFC and non-IFC investments: InCAF prefers to work with projects in which IFC

is an investor but will also consider non-IFC financed projects. For non-IFC

projects, the InCAF will look for well-established sponsors with access to

confirmed sources of conventional financing. Non-IFC projects will require

additional due diligence on project fundamentals.

- Environmental and social impact: all projects, including non-IFC financed

projects, must comply with IFC’s environmental and social policies and

guidelines. Projects that have large-scale adverse environmental or social

impacts will not be considered.

- Host country approval: the government of the host country will have to approve

the project. IFC can support the application of the project company to the

government for such approval. The host country will also need to have ratified,

or initiated domestic procedures to ratify, the Kyoto Protocol.

- Independent Verifications: the initial design of the project will need to be

validated by an Operational Entity, as required under the Kyoto Protocol. Once a

project is operational, the emission reductions produced by a project must be

verified and certified periodically by auditors.

21 InCAF will provide additional revenues to eligible projects

that generate emission reductions in developing countries. InCAF will make

future payments to the project over a period of 7-14 years upon annual

certification of actual greenhouse gas emission reductions. In return for these

payments, The Netherlands will receive the CERs. It is possible that InCAF will

consider advance payments under certain conditions. A contract between InCAF and

the project will specify the volume of emissions that are expected to be reduced,

the price agreed per ton of CO2 equivalent, and the crediting period.

22 Among the detailed measures, a selection will be made by

Inter-ministerial Committee for GHG reduction. Priority criterion will be the

cost-effectiveness of the various options.

23 The Mediterranean Renewable Energy Programme (MEDREP) was

launched as a Type II Initiative at the World Summit on Sustainable Development

in Johannesburg, following the recommendations of the G8 Renewable Energy Task

Force. MEDREP projects are being developed under the framework of bilateral

agreements between Italian Ministry of Environment and Territory (IMET),

Algeria, Egypt, Morocco and Tunisia. The pilot projects will represent best

practices to be replicated. IMET has allocated 8 million € to support the

start-up of the projects. Where possible, MEDREP projects will be structured as

carbon finance or green certificate transactions under the auspices of the Clean

Development Mechanism or Green Certificate Trading regimes

24 The types of projects may include small, community-promoted

plantations for timber, biofuel and other forest products. Though, these

plantations have to fit within a broader landscape design. In this sense, the

BioCarbon Fund does not exclude commercial scale plantations per se. However, in

most cases such plantations will not meet the CDM additionality requirement,

i.e. the plantation project could proceed without the incentives provided by the

CDM.

25 Main features of Italian Carbon Fund are:

- The fund supports projects eligible under the Kyoto Protocol’s CDM and JI

mechanisms through the purchase of credits;

- The fund is a public-private partnership currently endowed with US$ 15 million,

but with a target size of US$ 80 million;

- The fund will buy emissions reductions credits, but at the same time will

assist host countries in achieving sustainable development by leveraging

substantial investments in modern energy services and technologies, including

investments from the private sector;

- The fund is operational since January 28th, 2004;

- The income from payments received from the participants in the fund will be

held in a separate trust and used for capacity-building and research—thus

leading to the creation of supportive project approval systems in host countries;

- The Fund’s project portfolio is proposed to include support for a wide range

of technologies and regions, including China, the Mediterranean Region, as well

as the Balkans and the Middle Eastern countries.

26 Sri Lanka has recently (beginning of year 2005) signed a CDM

MoU (Memorandum of Understanding) with Canada.

Moreover, the British Government conducted a study on CDM projects titled "Initial

evaluation of CDM type projects in developing countries". Sri Lanka was one of

the countries studied. The reports can be found at http://www.surrey.ac.uk/eng/ces/research/ji/cdm-dfid.htm.

The UK Department for International Development (DfID) funded a project

coordinated by Ecosecurities to examine the developmental potential of the CDM;

to investigate strategies to encourage CDM investment flows in small to medium

developing countries; and to suggest ways that donors could get involved in

capacity building to facilitate the participation of these developing countries

in the CDM. The project had four developing country partners - Bangladesh,

Colombia, Ghana and Sri Lanka - for which country papers are available.

27 Yield of, e.g., gliricidia is considered to be about 30 tons/ha.

28 Pre-feasibility Study for 1 MW Biomass Power Plant & CDM

Project – Sri Lanka, P.G.Joseph, Team Leader National Technical Expert - PREGA

Pro

Pubblicato su

www.ambientediritto.it il 23/10/2006