AmbienteDiritto.it - Rivista giuridica - Electronic Law Review - Copyright © AmbienteDiritto.it

Testata registrata presso il Tribunale di Patti Reg. n. 197 del 19/07/2006

The

Influence of Regulation on Energy Infrastructure Development:

LNG Terminals in Italy*

FRANCESCO NAPOLI**,

SERGIO PORTATADINO***, ANTONIO

SILEO****

Abstract

In recent years, European gas demand has considerably grown, while the

internal production has decreased because of the progressive depletion of North

Sea fields. This has provided market operators with incentives to carry out new

import infrastructures, in particular new LNG regasification terminals. In

addition, also the new European regulation has played a very important role in

boosting new LNG investments, in particular with a general exemption from TPA

requirements.

However, regulation not only regards the remuneration of assets (ex-post), but

also the effective possibility to construct them (ex-ante regulation).

In a delicate and environmental-sensitive business such as the liquefied natural

gas, this implies time-consuming and expensive negotiation in order to obtain

the necessary authorizations with different government levels and agencies: a

bad ex-ante regulation may therefore neutralize the positive effects of an

incentive ex-post regulation.

Key words: gas demand, LNG Regulation, authorization process.

Introduction

Since 2000, year of the liberalization with the so called “Letta Decree”, the

Italian gas market has deeply changed, both from the point of view of the supply

side and the demand side.

First of all, let us consider the demand side. The big changes that have

occurred during the last seven years concern, in primis, the gas demand

growth, which has been extremely robust, at least until 2006 where it braked for

the first time.

Figure 1: Gas demand in Italy. Sources: AEEG, MSE (2007).

The reasons underlying this strong increase are:

• the construction of several

gas-fired power plants;

• the progressive depletion of the national reserves;

• the completion of the gasification of the country.

Of course, the annual overall consumption is also influenced by weather

conditions. This is in fact the explanation of the recent decrease: in 2006 the

day degrees have considerably decreased compared to the previous years.

Figure 2: Day degrees. Source: AIEE, 2007.

It is interesting to note the striking growth of the power generation demand.

This is due to the fact that, for environmental reasons, Italy has partially

dropped oil-fired power plants. In addition, there are strong local opposition

to the construction of clean-carbon plants and, as it is well known, Italy has

given up the nuclear technology after the Chernobyl disaster.

Figure 3: Gas consumption for power generation. Source: AEEG, 2006.

Now, let us consider the supply side.

The most important change in the gas industry is the brake-up of the old ENI

monopoly and the imposition to the incumbent of an anti-trust ceiling. This

constraint is twofold: on one hand, nobody can sell gas to more than 50% of the

final clients; on the other hand, ENI’s share of the overall gas inlet in the

Italian system cannot exceed a given amount (starting from 75%) which decreases

year to year until it will reach the minimum value of 61%. In other words, a

regulatory tool has been used in order to create room for new operators, which

could therefore freely import gas from producing countries and sell it to

wholesalers, retailers or even final customers.

Table 1: Gas importers in Italy. Source: AEEG, 2006

| Year | N° Importers |

| 1997 | 2 |

| 1998 | 3 |

| 1999 | 3 |

| 2000 | 3 |

| 2001 | 20 |

| 2002 | 20 |

| 2003 | 23 |

| 2004 | 23 |

| 2005 | 21 |

In addition, gas demand estimates forecast a further growth in the next years,

especially thanks to the contribution of the power generation sector.

Figure 4: Gas demand forecast. Source: AIEE, 2007.

So the intervention of the legislator, which has set the antitrust ceilings, has

allowed new operators to enter into the gas market; nonetheless, these new

companies have soon had to face the problem of infrastructures.

The point here has been that the international pipelines, that bring gas to the

Italian market, are all owned by ENI (or ENI holds the rights of usage). The

problem is that the Italian liberalization law does not say anything about these

infrastructures and it is also likely that it would be useless anyway, if we

consider that most of the pipelines lays in extra-EU countries or in

international waters.

Considering this, ENI has refused the access to third parties to its

international pipelines, by stating that they were already saturated. In this

way there was room for new operators on the market, but no way to reach it! The

new companies had, therefore, to buy gas from ENI before the Italian border,

paying a mark-up to the incumbent which had basically found a way to overcome

the antitrust ceilings.

With the double aim to avoid this situation and to turn Italy into a gas hub,

the Italian energy authority (AEEG) has decided to incentive new investments

with a new regulation which allows TPA exemption for new infrastructures (pipelines

and LNG plants). The result has been that 12 new LNG terminals and three new

international pipelines have been proposed.

Table 2: New pipelines. Sources: AEEG, 2006; AIEE 2007

|

PROJECT |

NOMINAL CAPACITY (Bcm/y) |

PROMOTER(S) |

STARTING DATE |

|

TAG Extension (Russia) |

6,5 |

ENI |

2008 |

|

TransMed Extension (Algeria) |

6,5 |

ENI |

2008 |

|

IGI (Greece) |

8/10 |

Edison, DEPA |

2010 |

|

GALSI (Algeria) |

10 |

Sonatrach, Edison |

2011? |

|

TAP (Albania) |

10 |

EGL Italia |

2012? |

|

TOTAL |

41 – 43 |

- |

- |

Table 3: New LNG plants. Sources: AEEG, 2006; AIEE, 2007

|

LOCATION |

NOMINAL CAPACITY (Bcm/y) |

PROMOTER(S) |

STARTING DATE |

|

Rovigo |

8 |

Edison Gas, Exxon Mobil, Qatar Petroleum |

2008 |

|

Off-shore Livorno |

3,75 |

Iride,ASA, Belleli, Endesa, Golar |

2009 |

|

Brindisi |

8 |

British Gas |

? |

|

Rosignano |

8 |

BP, Edison, Solvay |

? |

|

Gioia Tauro |

8/12 |

Iride-Sorgenia, Medgas (Belleli) |

? |

|

Off-shore Monfalcone |

8 |

Endesa |

? |

|

Trieste/Zaule |

8 |

Gas Natural |

? |

|

Taranto |

8 |

Gas Natural |

? |

|

Priolo |

8 |

Erg, Shell |

? |

|

Porto Empedocle |

8 |

Enel, Nuove Energie |

? |

|

Panigaglia |

4,5 |

SnamReteGas |

? |

|

Ravenna |

8 |

Atlas Ing |

? |

|

TOTAL |

88,25 - 92,25 |

- |

- |

If we look at the tables above, we can see how the LNG projects accounts for

more than double of the proposed new import capacity. So why this preference of

the investment promoters for LNG?

The answer must be found into the regulation that AEEG has set for the LNG

terminal ownership and management.

LNG Regulation in Italy

Regulation can be divided in two: ex-ante and ex-post. Ex-ante

regulation refers to the authorization process and the effective possibility to

construct the LNG plant. Ex-post regulation concerns the remuneration of the

investment and tariff-setting. We start our analysis from the ex-post regulation.

Ex-post regulation

The Italian Authority for Electric Energy and Gas (AEEG) regulates the access to

the terminal and the setting of the tariffs through its resolutions1.

The European Union2

and the Italian Parliament3

are other important normative sources.

The regulation of the regasification plant refers to two main aspects: the

access to the terminal and the tariffs setting. The first aspect is regulated by

the AEEG resolution n.°167/05, the latter by AEEG’s 197/05.

Then, each company managing a LNG receiving terminal issues a Regasification

Code, based on the AEEG’s resolutions, for the detailed management of every

aspects of the regasification plant.

The current regulatory regime will last from 1st October 2005 to 30th September

2008 and its main goals are the incentive of new investments and tariff

stability.

The main features of the new regulation are:

• higher WACC

• profit sharing criterion concerning the efficiency gain on OPEX;

• efficiency gain only on OPEX and not on CAPEX;

• Capacity/Commodity split equal to 80-20.

For what concerns new LNG receiving plants, the owner can ask the Ministry of

Industry for an exemption from the regulated TPA and therefore freely negotiate

(or retain) a share of the regasification capacity.

The exemption is granted by the Italian Ministry of Industry upon advice by AEEG,

if the new plant can enhance competition and security of supply through

diversification of gas sources.

All exemptions have to be considered case by case and they can result in an

exemption from TPA of, at least, the 80% of the nominal capacity for a

period of, at least, 20 years.

If, during the thermal year “t”, more than 20% of the exempted regasification

capacity is not utilized, the beneficiary user looses the exemption right for

the overall capacity starting from the thermal year “t + 1”.

On the other hand, regulated TPA applies to the old plant of Panigaglia and to

the non exempted capacity at new terminals.

The capacity allocation follows a priority order:

• at first, holders of take-or-pay

contracts signed prior to 10th August 1998;

• then, holders of pluriennial importing contracts different the ones above;

• finally, holders of annual importing contracts.

If the capacity is not enough to fulfil all requests, the available capacity is

allocated pro quota starting from the first priority class. “Use it or loose it”

clauses are introduced in case of unused capacity by an authorised operator.

At the beginning of each thermal year, regasification companies compute their

Allowed Revenues from which regasification tariffs are computed.

The allowed revenues RL are equal to:

RL = RAB*WACC + Depreciation + OPEX

Where:

RAB is the Revenue Asset Base;

WACC is the weighted average cost of capital;

OPEX are the Operative costs.

The RAB is the sum of the Net Fixed Asset (NFA) and the Net Current Asset (NCA).

NCA is equal to 1% of NFA. The computing of NFA follows the method of the

revaluated historic cost. The WACC (Weighted Average Cost of Capital) is

equal to 7,6%. The RAB is updated adding inflation, subtracting the relating

share of the amortization fund and eventually by subtracting the value of

divested assets.

80% of the revenues refers to the commodity charge and only 20% to the commodity:

this in order to invest users with responsibility concerning their capacity

booking. For the new investments, carried out from the second year of the

regulatory period, there is an additional charge. The annual efficiency gain

ratio for the energy-related charge is equal to 1.5%.

There is a guarantee mechanism over the capacity revenues, which cover 80% of

the related annual revenues (72% of the overall revenues).

On the basis of this rules issued by AEEG in its resolutions, the regasification

companies propose a tariff scheme for their terminal. This scheme is verified by

AEEG and eventually approved; otherwise AEEG will issue a new and definitive

tariff scheme in behalf of the regasification company.

In conclusion of this paragraph we want to underline the importance of the “ex

post” regulation which, through a guarantee mechanism on revenues, a favourable

WACC and TPA exemption aims at stimulating new investments. The number of the

proposed new LNG terminals seems to confirm the achievement of this goal.

But to make policy really effective, we have also to consider the “ex ante”

regulation, which is often underestimated in investment decisions of operators.

Ex-ante and ex-post regulations need to be consistent in order to make the

market achieve the regulator’s objectives.

Ex-ante regulation

The European sources

The European Union has enacted some relevant directives concerning the

authorization of regasification facilities. Some provisions regard the role of

such energy facilities within the liberalization of the European natural gas

market, while others concern their environmental impact and safety, in

particular:

• market integration and

Trans-European networks;

• security of energy supply and promotion of efficiency;

• environmental protection and energy policy sustainability;

• safety of citizens and workers.

Some European directives contain pertinent provisions to regulate the

authorization of energy projects. As far as regasification facilities are

concerned, the following directives should be mentioned:

• directive on internal gas market

(2003/55/EC);

• directive on the Environmental Impact Assessment (“EIA”) (85/337/ECC, amended

by directive 97/11/EC);

• directive on the Strategic Environmental Assessment (2001/42/EC);

• “Seveso III” directive (directive 2003/105/EC on the control of dangers caused

by serious accidents linked to certain hazardous substances).

Italian laws on the authorization of regasification projects

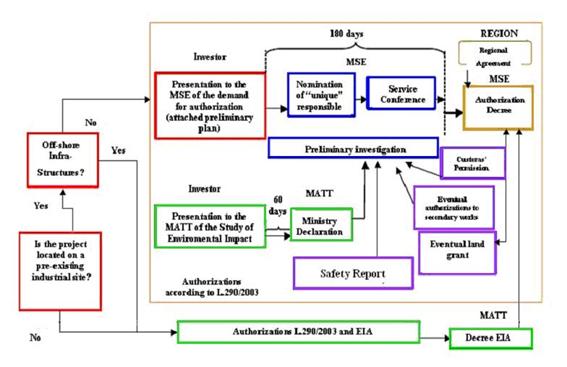

First of all, we need to underline that the reform of the art. 117 of the

Italian Constitution in 2001 has given parallel competences to the Central

States and the Regions in matter of energy and environment.

At a government level, it should be pointed out that the Italian legal system,

on the one hand, regulates the authorization process for the construction and

operation of regasification facilities and, on the other hand, transposes the

European directives on environmental protection and safety.

The laws regarding the authorization process for regasification terminals is

made more complex by the presence of different procedures whose enforceability

depends on the location of the facility subject to authorization.

Currently, there is not one single authorization procedure. The possible

procedures are as follows:

• the plants identified by the

“Comitato Interministeriale per la Programmazione Economica” (CIPE) should be

subject to the authorization under the target law. However it has never been

applied, with the exception of the Brindisi facility, which falls within the

scope of Art. 8 of law 340/2000;

• the plants to be built in pre-existing industrial areas are subject to the

authorization under Art. 8 of law 340/2000;

• offshore plants or those to be built in state-owned areas (coasts) are subject

to the standard authorization procedure;

• as regards the plants to be built within autonomous regions, the procedure

shall be in compliance with regional laws.

The transposition of European directives is important in that it turns into

necessary procedures for the authorization of regasification facilities to the

purpose of the project’s environmental compatibility.

Also regions play a very important role within the authorization process for

regasification facilities: in fact, the authorization process requires also the

regions’ agreement for the construction of this infrastructures4.

Authorization process for regasification facilities

The authorization process, with the exception of special-status regions, is

characterized by:

• the possibility contemplated by art. 8 of Law 340/2000, to exclude the EIA for

facilities to be entirely build in pre-existing industrial areas, and replace it

with the submission to the Italian Ministry of the Environment (“MATT”) of an

environmental compatibility study, on which the MATT should pronounce itself

within 60 days.

• the need to obtain authorizations and permits from a series of entities (port

authorities, Customs, Ministry of the Environment, etc.) .

• The power of veto of the Regions.

The authorizations to the construction and operation of regasification

facilities are issued by the Italian Ministry of Economic Development (“MED”),

by mutual agreement with the MATT. However, as regards regasification facilities,

there is not any consistent and single attempt to put all authorizations

together to form a single measure, as it happens for large thermoelectric power

stations.

Law 290/2003 sets down the authorization needed for the construction of

regasification facilities. MED authorization should be accompanied in any case

by:

• Government concession for the plants to be built in state-owned areas (articles

12-18 Law 84/94);

• authorization of any connected facilities and works needed for the operation

of the facility and subject to a separate authorization process.

• authorization according to Seveso directive (L.D. 334/1999 updated by L.D.

238/2005).

Authorizations from the following authorities are also needed:

• from the port and sea authority (art. 14 Law 84/94, art. 48 and art. 52 of the

Code of Navigation),

• from Customs.

An exception is represented by those

plants considered of “public interest” by a decree of the Ministry of Production

Activities (now “MED”). Following the law 443/2001, four facilities were

identified for this reason by CIPE: “Offshore Adriatico” (Rovigo), Taranto,

Brindisi and Vado Ligure. Such facilities could benefit, under the law, from a

simplified authorization process: in fact the authorization must be given within

a short term (180 days).

Finally, art. 8 of Law 340/2000 streamlined the authorization process for the

regasification facilities to be built in pre-existing industrial areas:

currently, there is not one single authorization procedure.

The standard procedure is as follows:

• the plants identified by CIPE should be subject to the authorization under the

“Target Law5”. However

it has never been applied, except for Brindisi facility, which falls within the

scope of Art. 8 of law 340/2000;

• the plants to be built in pre-existing industrial areas are subject to the

authorization under Art. 8 of law 340/2000;

• offshore plants or those to be built in state-owned areas (coasts) are subject

to the standard authorization procedure;

• as regards the plants to be built within autonomous regions, the procedure

shall be in compliance with regional laws.

• finally, L.D. 190/2002, art. 1, establishes another simplified procedure for

“production plants and private facilities with a strategic interest”.

Regasification facilities fall under such definition. However, such simplified

procedure has not been applied yet.

As a matter of fact, the sole difference between the first two procedures and

the standard one, is the non-compulsoriness of EIA rules. All that in accordance

with Law 239/2004, (art. 1, paragraph 60), according to which “the procedure for

the assessment of the environmental impact applies to the creation and

development of liquefied natural gas regasification facilities including the

works related thereto, except for the provisions of Law 443/2001, and art. 8 Law

340/2000”. However, it should be said that, with the exception of Brindisi, the

EIA procedure has always been implemented.

The “Service Conference”

The process through which the authorization to the construction and operation of

a regasification facility is granted or denied uses the instruments and

procedures provided for by the standard provisions of the administrative

procedure, in accordance with Law 241/1990 and following amendments.

The Service Conference is considered for the authorization processes for

investments in the energy sector as the most important instrument of the process:

it puts together in a single debate the opinions and requests of the entities

involved6.

Art. 14-bis regulates the preliminary service conference, which is convened in

the event of particularly complex procedures in order to clarify the

pre-requirements and formalities, which each administration involved deems it

necessary to the end of their favorable opinion.

The law provides for and regulates the case where there is no agreement among

the members participating in the conference.

Anyone must justify its dissent, inherent in the subject of the conference,

expressed during the conference itself, and give suggestions for its resolution.

A decision must be made within 30 days (extensible to 60), after which the

Cabinet is called upon to pronounce itself within the following 30 days.

Figure 5: Summary authorization flow-chart.

Conclusions

In conclusion we want to underline how, in order to be really effective, an

energy policy needs to concern both the ex-ante and ex-post regulations. The

Italian case is an example of what happens when the two sides of regulation are

not well coordinated. In order to provide the market with incentives for new

investments, the Italian energy authority has established a favourable ex-post

regulation, but a complicated and blur ex-ante regulation seems to avoid the

construction of the needed infrastructures. This situation represents an extra

risk factor which damps new investments and distorts competition.

Problems with ex-ante regulation in Italy arose with the reform, in 2001, of the

Art. 117 of the Constitution, which gave parallel competences to the Regions and

the Central State in matter of energy and environment policies. Because of this

reform, all the government bodies, at all levels (from municipalities to the

Central State) are involved in the authorization process and can stop it in a

way or in another7. In

addition, Regions have the veto power.

Another critical point is represented by the environmentally-related conflicts

involving citizens and local entities.

Besides NIMBY (“Not In My Back Yard”) syndrome, which has affected our country

from north to south, there have been also cases of BANANA (“Build Absolutely

Nothing Anywhere Near Anything”) syndrome.

Italy’s peculiarity in this matter is given by the disagreement of opinions

between Government and regions, which often degenerates into a real clash, even

between members of the same political group.

The key policy indication is that the European Commission and the Forum of the

European Energy Regulators must face also the problem of designing a common and

stable ex-ante regulation, in order to neutralize possible negative effects on

competition of the authorization process in the different Member States.

In particular, a “social dialogue” policy should be pursued: in other words, it

is necessary to achieve the widest possible consensus, but not necessarily the

unanimity of all the stakeholders. In fact, given the importance of this kind of

infrastructures, both in term of market efficiency and security of supply, it is

desirable the presence of a strong final decision maker.

We finally want to mention the Brindisi LNG terminal: it was entered in 2003

budget for € 390 million, but then, due to authorization problems, it became €

500 million in 2005 financial statements and finally € 540 million in 2006.

References

European Commission (2007)- DG Competition report on energy sector inquiry.

A. Sileo and H. Franchini (2006), Politiche energetiche e ambiente,

Aracne Editrice, Italy.

A.A.V.V., (2006),1° Rapport,o di informazione semestrale ONIPE, Osservatorio

Nazionale sugli Investimenti e sui Progetti nell’Energia, Politecnico di Milano

e REF, Milano.

Agricola B., (2005), Le attività e gli strumenti della Commissione Speciale

per la Valutazione di Impatto Ambientale, Roma.

Barroccini A.C., Belvisi M., (2006), Orientamenti giurisprudenziali in

materia di VIA, Agenzia per la Protezione dell’Ambiente e per i Servizi Tecnici,Roma.

http://www.autorita.energia.it/

http://www.sviluppoeconomico.gov.it/

http://ec.europa.eu/comm/competition/sectors/energy/inquiry/index.html

_____________

* 9th IAEE

European Energy Conference “Energy Markets and Sustainability in a Larger Europe”

.

** DEPT. I.C.M.M.P.M – Università La Sapienza, francesco.napoli@uniroma1.it.

*** IEFE - Università Bocconi, sergio.portatadino@unibocconi.it.

**** IEFE - Università Bocconi, antonio.sileo@unibocconi.it.

1Resolutions n.° 120/01; 193/01; 91/02; 119/03; 184/04; 52/05;

167/05; 178/05; 197/05.

2 Directives n.° 98/30/CE; 03/55/CE.

3 Law n.° 164/00 (Letta decree); law n.° 239/04.

4 They have an advisory function (see D. lgs. 152/2006).

5 The “Target Law” is a simplified process introduced by the

Italian Government.

6 It should be noted that pursuant to art. 14, convening the

Conference is not mandatory: in fact, if all the public administrations,

involved in the process, give their favourable opinion within 30 days, the

Conference need not to be held at all. However, paragraph 4 lays down that “when

the activity of a private entity is subject to the approval of more public

administrations, the Service Conference is convened by the competent

administration for the adoption of the final measure”.

7 Both in the Service Conference and with an appeal to the

Administrative Court